The Case for Catholic Education

The Case for Catholic Education: Why Parents, Teachers, and Politicians Should Reclaim the Principles of Catholic Pedagogy

Reviewed by Benjamin V. Beier

In his The Case for Catholic Education: Why Parents, Teachers, and Politicians Should Reclaim the Principles of Catholic Pedagogy, Dr. Ryan Topping has provided a fine apology for Catholic education. This short book provides an accessible, provocative, and clear account that will benefit all of the titular audiences as it offers a “set of principles that might guide any genuine renewal of the Catholic culture in our homes and in our institutions” (10).

The book is organized into six chapters and two appendices, and focuses on the education of young adults from roughly the ages of 13-21 (19). The first two chapters look at the past and present standing of Catholic education in North America; the next three chapters offer an account of the aim (chapter 3), methods (chapter 4), and content (chapter 5) of an authentically Catholic education; and the final chapter concludes, noting signs of renewal and hope in the educational landscape.

Let me summarize each of the chapters more fully, reflect on the book’s apparatus, and then offer some final remarks. The first chapter, which provides a brief history, largely follows Christopher Dawson’s account of our educational crisis and points to two errors. The first error is intellectual: many Catholic schools have lost confidence in the truth and evaluate success according to a reductive, purely utilitarian standard. Also, and this is the second error, many schools have lost a Catholic culture or rootedness in the stories, smells, images, and the like that shape the moral imagination in immediate and often intuitive ways. Chapter two builds on this critique by using qualitative sociological data to show that, while Catholic schools may still be able to teach reading, writing, and arithmetic well, they are largely failing to pass on the faith and to help students avoid destructive behaviors.

With that background, Topping seeks to provide principles for renewal of Catholic education. Topping is clear throughout the second half of the book that the principles for regeneration are minimal and the enactments of renewal can take many different beautiful, complementary forms. In chapter three, he identifies the ends of a Catholic education: happiness (ultimate aim), culture (remote aim), and virtue (immediate aim). In light of these goals, Topping shows that Catholic education will often have to depart from current secular philosophies of education which, at bottom, reject the desirability and/or achievability of these goals. Topping argues, focusing on the ultimate aim, that at the heart of the matter is an adequate philosophical anthropology or view of the human person. Contemporary progressive education often seeks to lead students to a freedom of expression, whereas Catholic education seeks to give students a freedom for excellence by which to achieve happiness. One wishes that, while maintaining the book’s attempt to be a primer, Topping could have given even a little bit more attention to the other two aims: culture and virtue. He appears to think that Catholics and those who assent to a different educational philosophy will find more common ground in the goals of virtue and culture. This is likely true, but when Topping speaks of virtue, it is not fully clear whether he means skills only (a synonym he uses on page 39) or intellectual and moral virtues. Moreover, I’m not sure that Catholic and secular philosophies of education still agree on the ability of education to cultivate the mind and on the desirability of education shaping the manners of the pupil. At the very least, what makes up the cultured human being is now less agreed upon than when Newman proposed the end of education be the cultivation of a gentleman.

Chapter four turns to issues of method by which to achieve the aforementioned aims. Topping insists that we must recover the truth that parents, not educators or the state, are the primary educators of their children, and that the child while fundamentally good has a weakened will, darkened intellect, and disordered passions. The reality of concupiscence in students requires that they be formed and guided, rather than just allowed to express themselves. Topping points more particularly to the need for a method in which students learn through imitation and, drawing from the Baltimore Catechism and Ratio Studiorum, offers an illustrative examples of how one might employ this methodology.

This account of method naturally leads to reflections on content in the penultimate chapter. Topping recommends the teaching of the seven classical liberal arts (grammar, logic, rhetoric, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, music) as well as the good, and eventually, the great books. Rather than giving an account of exactly how these subjects and books will fit together, the book provides reflection on the developmental ages of students and what sorts of subjects and texts they will be ready to encounter to shape their intellects, imaginations, and spirits at a given stage. The book’s foreword says that Topping has a “bias” toward classical education. The word “bias” may have a negative connotation, but as one sympathetic to classical education myself, I found the account compelling and adaptable. Topping’s rich description of the power of liberal arts education may qualify his earlier assessment that Catholic schools usually teach reading, writing, and arithmetic well, yet he avoids being unnecessarily prescriptive and calls for prudential discernment from parents and teachers as they select content and enact liberal education principles.

To this point the book has articulated an unhappy present and sad history of Catholic education in North America, as well as an ambitious program for renewal that might leave some readers, especially those who are new to these ideas, a bit overwhelmed. Topping does not leave such readers in a state of bewilderment. Instead, he closes by briefing the reader on institutions (not only schools and universities, but also ancillary organizations) where a renewal of Catholic education has begun. A reform is possible; begin! Moreover, the book finishes “painting a picture . . . of two girls” (82), an anecdote that shows the preceding pages aren’t just theoretical; rather, the choices of Catholic educators (parents, teachers, politicians, and clergy) shape the lives of individual children and have the potential to set a student on the road to destruction or to flourishing.

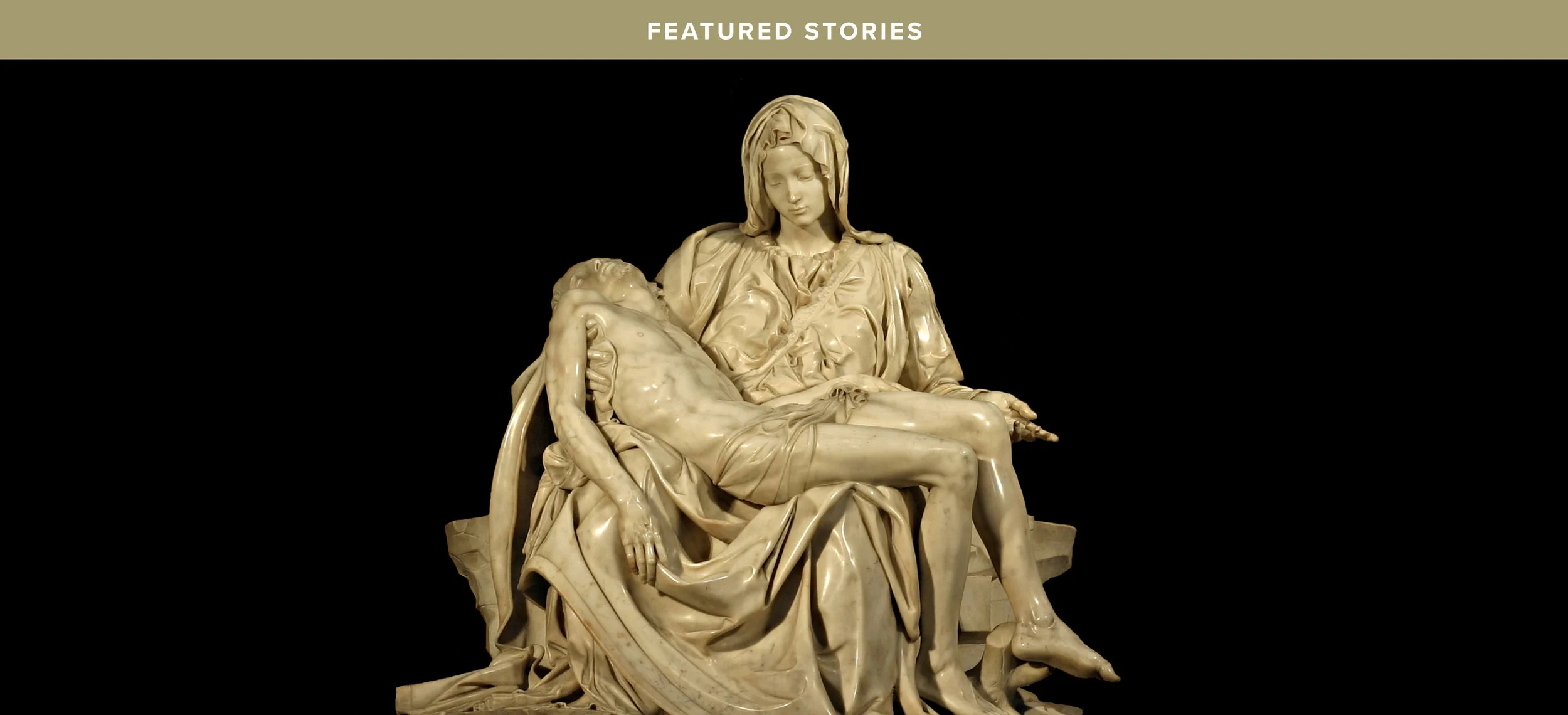

I have characterized this book as a primer and an apology. It is very accessible and offers an appendix of discussion questions and recommendations for further reading, as well as inset quotations and rich images. Like most Angelico Press books, the edition itself is handsome. The prose is lively and, in certain moments, acerbic while remaining largely generous to opponents of good will. The discussion questions maintain this spirit of exchange, often encouraging readers to reflect on their own subjective experiences.

The work has already garnered much praise, excerpted at the book’s beginning, and there is a largely complimentary foreword by Sr. John Mary Fleming, O.P., Executive Director for Catholic Education at the USCCB. I found the book particularly compelling in its willingness to blend philosophical, qualitative argument with quantitative data, and in doing so, Topping will be able to reach many different audiences. Near the beginning and the end of the book, Topping quotes Pope Benedict XVI’s exhortation that Catholic schools be “a place to encounter the living God.” All told, his treatment of the principles and of the past, present, and future of Catholic education in North America is one that seeks this goal, articulated by Pope Benedict, above all the rest. May this fine little book find its way into the hands of its intended audiences, and may more and more schools and educators see that a reclamation of Catholic pedagogy is needed. Christ, King of the Universe, cannot be squeezed in to existing secular curricula and methods as if He were an elective.