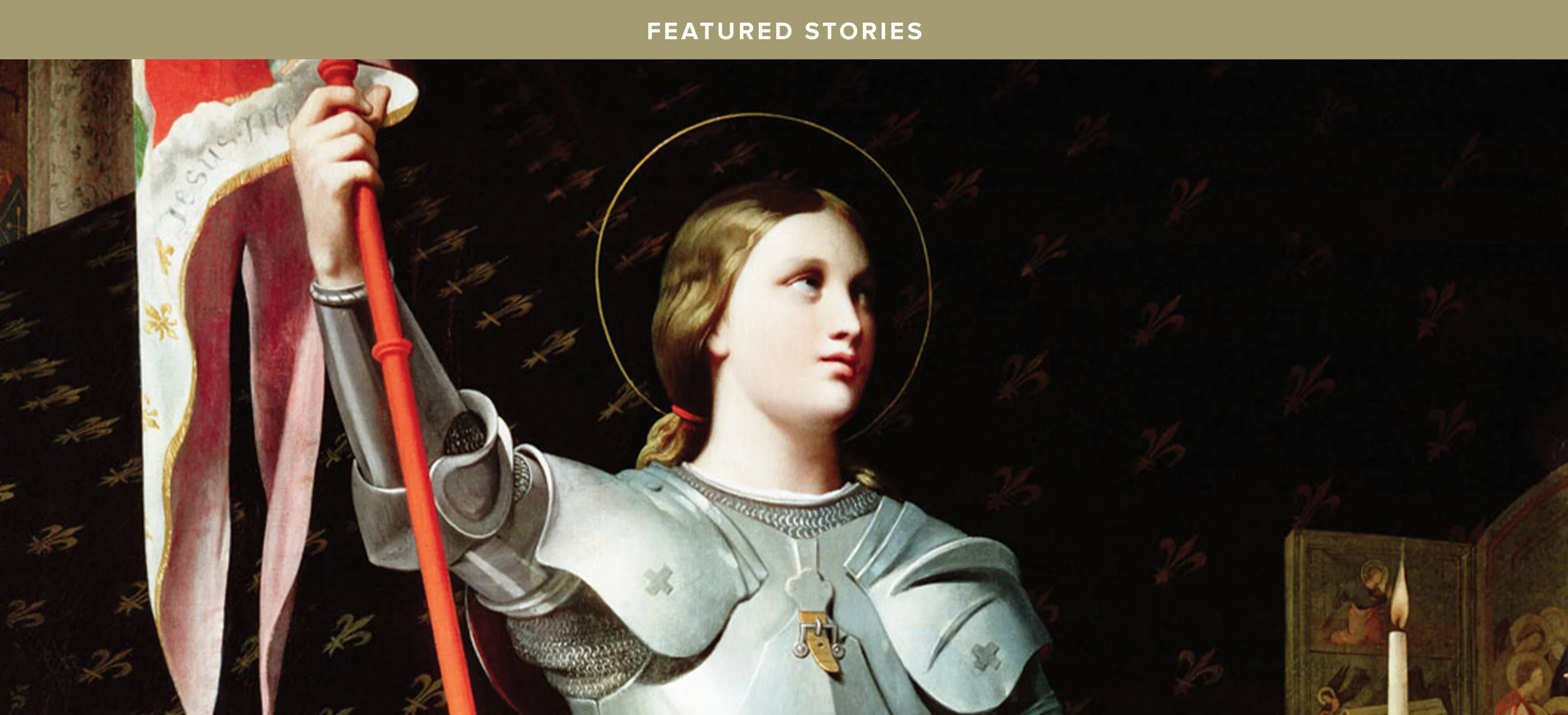

St. Joan of Arc

The story of Joan of Arc is preposterous. In what reality could a teenage girl approach the would-be king of her country with an account of angelic and saintly visitations and persuade him to give her troops to fight against a vastly superior army – and, after he agrees, she wins? It’s the stuff of myth and legends, but not history.

Except that it is history. In fact, it is one of the most well-documented cases of its time, with detailed eyewitness accounts of everything that happened with, and to, the “Maiden of Orleans,” the peasant girl of Domremy. There are transcriptions of her two trials. The first declared that she was a heretic, allowing her to be burned at the stake; the second posthumously declared that she wasn’t. In her story we see bravery and cowardice, political intrigue and ecclesiastical subterfuge, loyalty and betrayal, vision and blindness, hope and despair, the best and worst of our human condition.

Little wonder, then, that a glance at the artistic record shows the many ways the preposterous peasant-girl-who-became-a-warrior story has quickened the imaginations of artisans across all spectrums of creativity. Paintings, sculptures, operas, musicals, plays, films and television productions have all attempted to capture and reinterpret the story of Joan.

Apart from short paragraphs in books about the saints, or prayer cards, many of us know about Joan through Mark Twain’s Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc. Some consider it the best novelization of her life. Surprisingly, Twain himself considered it his finest work. Many other authors have attempted to tell her story through fiction, myself included, though her character is often filtered through sensibilities that were not of her time. For some, she is a feminist. For others, a representative of a working-class heroine along a Marxist vein. For Protestants, she is as a foreshadowing of a type of Martin Luther.

Voltaire wrote a satirical poem about her, which received a rebuttal fifty years later by German poet Friedrich Schiller.

Joan is no stranger to theatrical productions. William Shakespeare gave her a prominent place in his Henry VI series. Saint Therese of Lisieux wrote two small dramas about her, focusing on her visions, to be performed on various feast days for her religious community (St. Therese herself initially played Joan). George Bernard Shaw directed his particular style to her in Saint Joan, which later became the basis for Otto Preminger’s 1957 film version, scripted by the so-called “Catholic novelist” Graham Greene.

Playwright Maxwell Anderson gave his own interpretation of the story through Joan of Lorraine, leading to a Tony Award for its star Ingrid Bergman, and opened the door for her to portray the saint in a big-budget film version of the play a year later. Directed by Victor Fleming, known for The Wizard of Oz, critics have called it the best film version of Joan. Curiously, Ingrid Bergman would appear as Joan on film in 1954 for her then-husband Roberto Rossellini, the Italian director.

Some would argue that the most powerful film rendering of Joan came during the Silent Era from Danish film-maker Theodor Dreyer. His The Passion of Joan of Arc, released in 1928, blends a harsh realism with stylistic imagery to show Joan, not as a victorious girl on the battlefield, but a young girl enduring torturous interrogations. Long, lingering close-ups of her face give us an intimate view of a saint-in-the-making as she attempts to reconcile the attacks of her tormentors with the calling of God that led her to them. The effect is oppressive and claustrophobic, until she is finally taken out to be burned at the stake (which is seen in its raw brutality).

Not surprisingly, the last year of the 20th century gave us two opposing views of Joan. A television mini-series featured LeeLee Sobieski presented a straight-forward telling of Joan’s life, with an all-star cast and the latest special-effects to highlight the battles. It won multiple awards but, alas for me, Sobieski’s performance was unconvincing. She seemed more like a modern girl dropped back in time than a girl from the time itself. Meanwhile, French director Luc Besson presented Joan as a woman whose visions were not God-given, but merely the result of mental instability.

Another French director, Bruno Dumont, created two unusual films about Joan in 2017 and 2019. The first was an odd musical, integrating heavy-metal styles with the story of Joan as a young girl. Its star, Lise Leplat Prudhomme, was the right age and had the right look for Joan. The second film departed from the musical format and gave us the now-teenage Prudhomme as Joan after her capture. The actress’ performance was praised by some critics, but the overall film left most viewers flat. The main complaint was that the director could not seem to decide if he was producing a drama, a comedy, or a tragedy.

Against that artistic backdrop, I wondered anew about Joan as I began to write The Warrior Maiden (the second novel in the Virtue Chronicles series from the Augustine Institute). I opted to return to the original transcripts from the two trials, hoping to let her speak for herself. I was surprised to encounter a young woman, very much a teenager in her sensibilities and occasional emotional outbursts, but mature in the simplicity of her convictions. There was no artifice or guile in her determination to accomplish what God – through His messengers – had told her to do. If she was impatient, it was because she couldn’t understand why those in power did not share her vision. Sadly, her political naivete put her at the mercy of unscrupulous men, even while her determination gave those same men military unimaginable victories. She succeeded in the impossible: seeing the estranged Dauphin officially crowned as king and driving the English army out of long-held areas of France. She obeyed her God and, like her Lord, was betrayed by men. The whole thing was preposterous.