What’s Wrong with Time-Out Tabernacles

If a parish were to set about raising funds for a new tabernacle built to resemble the Ark of the Covenant, I would gladly donate. The Ark held, among other things, an omer of manna. We would do well to better remember such parallels between the Old Covenant and the New, lest we lose our roots and, like the Israelites, wander aimlessly in our own postmodern desert.

Yet many parishes do not have such aims. Instead, they relegate the tabernacle to a corner (as if Our Lord is a naughty child in time out) or, worse yet, to a separate room. The presider’s chair--and not the Holy of Holies--is all too often the center of attention.

A brief case in point: At the local parish, the tabernacle is positioned where a side altar once stood. It is impossible to gaze at it and the crucifix in the main part of the sanctuary at the same time. I noticed this one Sunday, and I could not help but wonder at this symbolic divorce. If the tabernacle is not located front and center, but instead separated from the image of Christ crucified, the Sacrificial Lamb, it takes away a physical reminder of Who dwells, fully present, in the Eucharist. The tabernacle becomes a mere storage cabinet, out of sight and out of mind. Most of the local parishioners genuflect to the altar when they enter and exit, not the tabernacle. How many other parishes across the nation have this problem?

When those of other faiths visit a Catholic church, the first thing they should see is that we clearly, unapologetically worship God in the Holy Eucharist. What do they think when they see us put God in a box to the side so that Father Friendly and his crew of lay ministers can stand front and center?

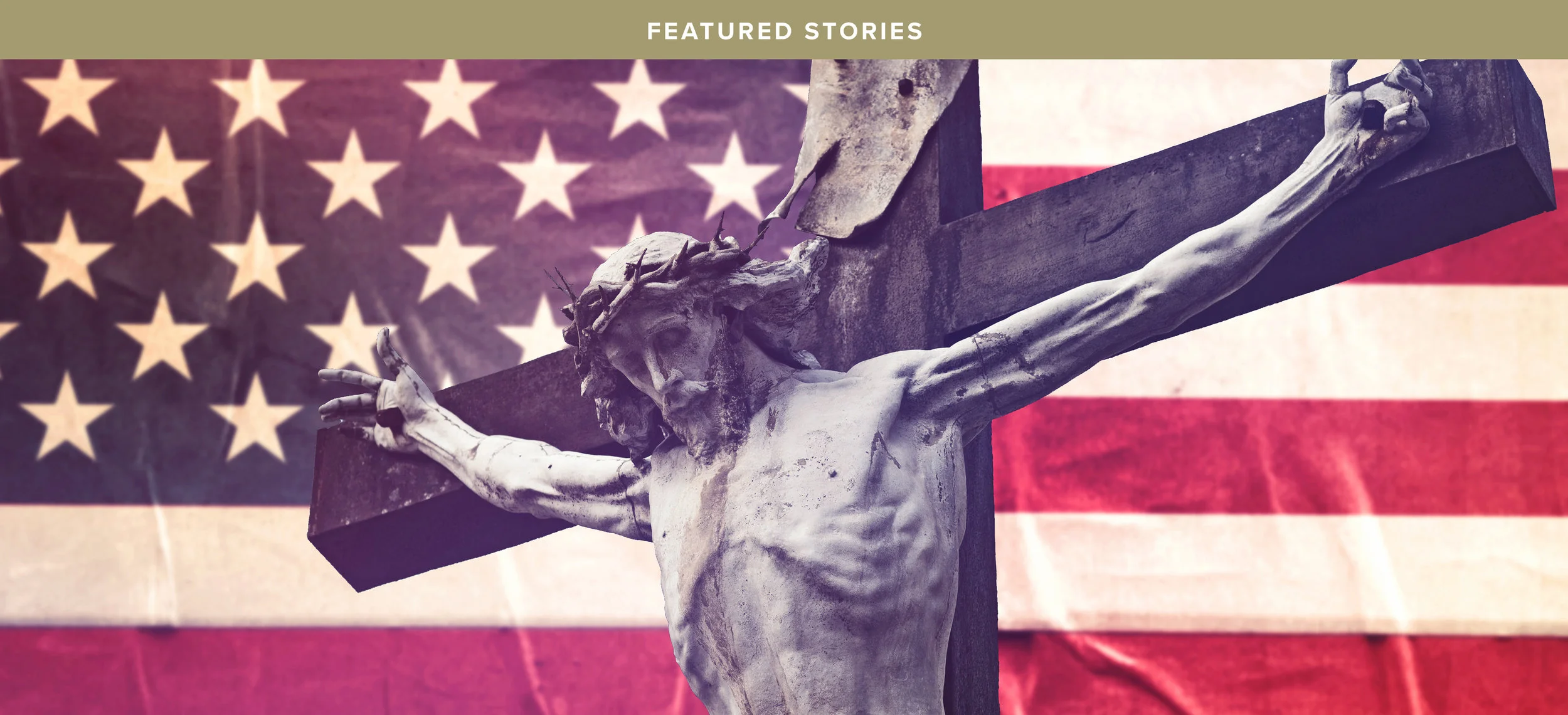

A further example of the spiritual degeneration that accompanies the removal of the symbolic is the general aversion that Protestants have to crucifixes. Now, there is nothing wrong with plain crosses. We Catholics use them frequently, too. But I cannot help but wonder at how the most informal, feel-good denominations have nothing but bare crosses. (The Catholic equivalent would be the chimera dubbed the “resurrec-cifix,” a cross with a risen Jesus fixed to it.) Without the bloody, broken Corpus, we can easily lose the sense of the gravity of sin and the passionate love of God. A bare cross morphs in an elongated plus sign, a Christian thumbs-up that says, “You’re OK!” It has no more meaning than the clichéd peace symbol of the hippies.

Let us contrast the spiritual vagueness of resurrec-cifixes and time-out tabernacles with the solid symbolism of good liturgical architecture. I will use as my example a parish I visited in Denver, Holy Ghost parish.

Holy Ghost Church, Denver, CO

At Holy Ghost (hands down one of the most beautiful churches I’ve visited), the tabernacle is situated on the high altar under a beautifully carved crucifix, and over this is a wooden baldachino. Flanked by statues of John and Mary carved from the same wood, the crucifix is a thing of noble simplicity. It catches the eye and invites meditation on Our Lord’s last moments, but more than that, Jesus’ downturned head directs the eye down past the ring of clouds and cherubs that form a monstrance to the prominent tabernacle where He resides.

This graceful, tower-like arrangement provides a rich opportunity for contemplation. At the foot of the tower, the Ground of it all, is Christ Himself, in Whom “we live and move and have our being,” in Whom our lives must be rooted. Next is the monstrance, the sacred vessel in which the Lamb of God is placed during Adoration and Benediction for the faithful to worship and behold. Its design (the aforementioned ring of angels and clouds) reminds one both of the magnificent Holy Ghost window in St. Peter’s Basilica and of the fact that we await the day when we shall “see the son of man coming on the clouds of heaven.” Finally we move from where the Lamb of God is lifted up in Adoration to where He was lifted up on the cross, “a stumbling block to the Jews and foolishness to the Gentiles,” paradoxically defeating death by tasting it, redeeming us by His Blood, the Blood of which we drink every time we receive the Eucharist.

Aside from this obvious connection between the sacrifice (re-presented in an unbloody manner at every Mass) and the Victim in the tabernacle, another thought struck me while gazing at this crucifix and pondering the Passion. The cross itself was superimposed on a circle so that a quarter of the circle separated each of the arms of the cross. It looked as if Jesus were bearing the world on his shoulders, a dying Atlas. And then I realized that in truth He was bearing something much heavier than Atlas’s mammoth burden. He had on his back not the world, but the sins of the world, past, present, future. Our Lord loves us, and He was right there in front of me, truly present, reposed in the tabernacle at the foot of the cross. How could a resurrec-cifix and a time-out tabernacle facilitate such a meditation?