Who is the Great I Am?

I am the great sun, but you do not see me,

I am your husband, but you turn away.

I am the captive, but you do not free me,

I am the captain you will not obey.

I am the truth, but you will not believe me,

I am the city where you will not stay,

I am your wife, your child, but you will leave me,

I am that God to whom you will not pray.

I am your counsel, but you do not hear me,

I am the lover whom you will betray.

I am the victor, but you do not cheer me,

I am the holy dove whom you will slay.

I am your life, but if you will not name me,

Seal up your soul with tears, and never blame me.

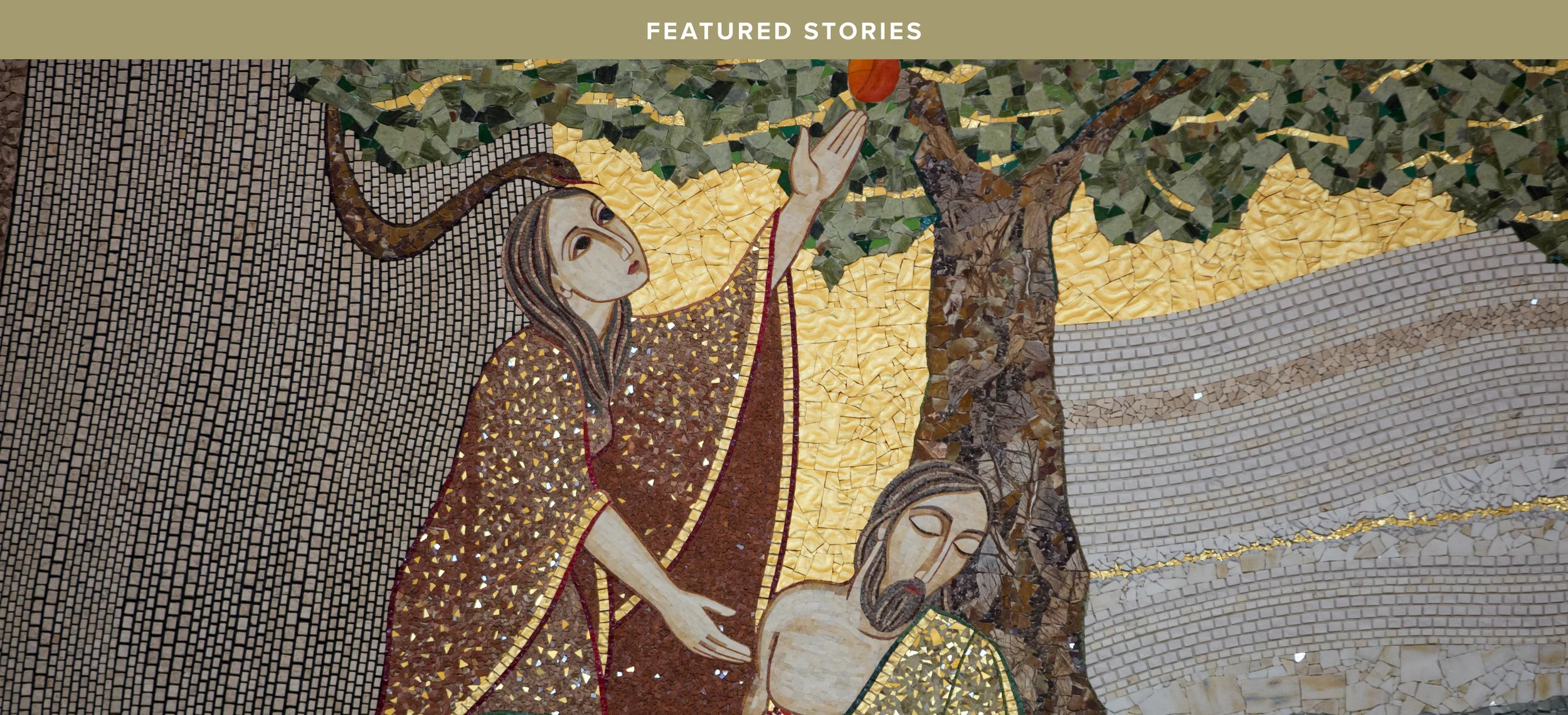

It is over sixty years since the Cornish poet, Charles Causley, published his profound sonnet, “I Am the Great Sun”. Yet, as is the way with great art, its power is as undiminished by the passage of time as is its meaning. The Great Sun is of course God Himself, the Great I Am, to whom we owe our very existence. And yet, as the poet laments, we do not honour the debt. On the contrary, as all of human history has demonstrated, we continually spurn Him, either by denying Him, defying Him or, perhaps worst of all, by simply forgetting all about Him. The truth is that we replace the I Am, who always is, with our own ridiculous “I am”, making ourselves the centre of our own diminished and ever diminishing cosmos, which shrivels as surely as we do. This pathetic inversion of the true order of things is as old as sin itself. It was the sin of Satan, who preferred to rule in his own self-made hell than to serve the One who gave him his being, and it was the sin of our own first parents who preferred the seductive lie that they might be gods to the God-given gifts of life, love and paradise that had been lavished on them.

Incidentally, and lest we forget, the sin was not to be found in the fruit that our first parents ate, which was created by God and was therefore good, but in the malicious choice to eat it in defiance of God’s commandment. The sin was not in the fruit but in the plucking. The problem is in the malicious nature of the choice. Nor was the sin in the freedom of choice that Adam and Eve employed in making their decision. The freedom to choose was given by God, as a manifestation of His own Image in Man, and is therefore good. It is not the freedom that is the problem but its abuse. The fact is that we do have the right to choose, given to us by God, but we also have an irradicable responsibility to choose the right. Failure to do so has disastrous consequences, as the tragic fall of Satan and our first parents demonstrates. And as the tragic fall of our own deplorable epoch demonstrates all too clearly.

The problem with relativism, the religion of the Zeitgeist, is that it enshrines truth in the I am of our own self-enclosed egos and not in the I Am who always is. If I am the arbiter of the truth of my own self-centred cosmos, I am condemning myself to a shrinking and shriveled microcosmos in which I am doomed to the loneliness that the ego creates. Worse still, I am condemning my neighbor to the consequences of my own selfishness.

The other problem that the microcosmos of relativism causes is that it inevitably decays as it ages. Relativism is attractive when we are young and full of life, enabling us to wreck our own lives and the lives of others on the rocks of our egocentrism, but it wears thin as we grow older and the spectre of mutability and mortality raises its head. As we realize that we are not in control of our own ego-cosmos and that the I amis doomed to become the I was, we become embittered and cynical. The only escape from such bitter shriveling is to see the memento mori, the reminder of death, as a gift to be accepted and embraced, or, in Christian terms, as a cross to be carried. And this is only possible through an act of humility, which is nothing less than the abandonment of our own I amand an acceptance of the Great I Am who magnifies who we truly are, the I am in Him. It is only then that we can reach the wisdom of humility that we see in holy men, such as G. K. Chesterton, who, when asked what was wrong with the world, answered I am.