The New Evangelization needs a New Hellenization

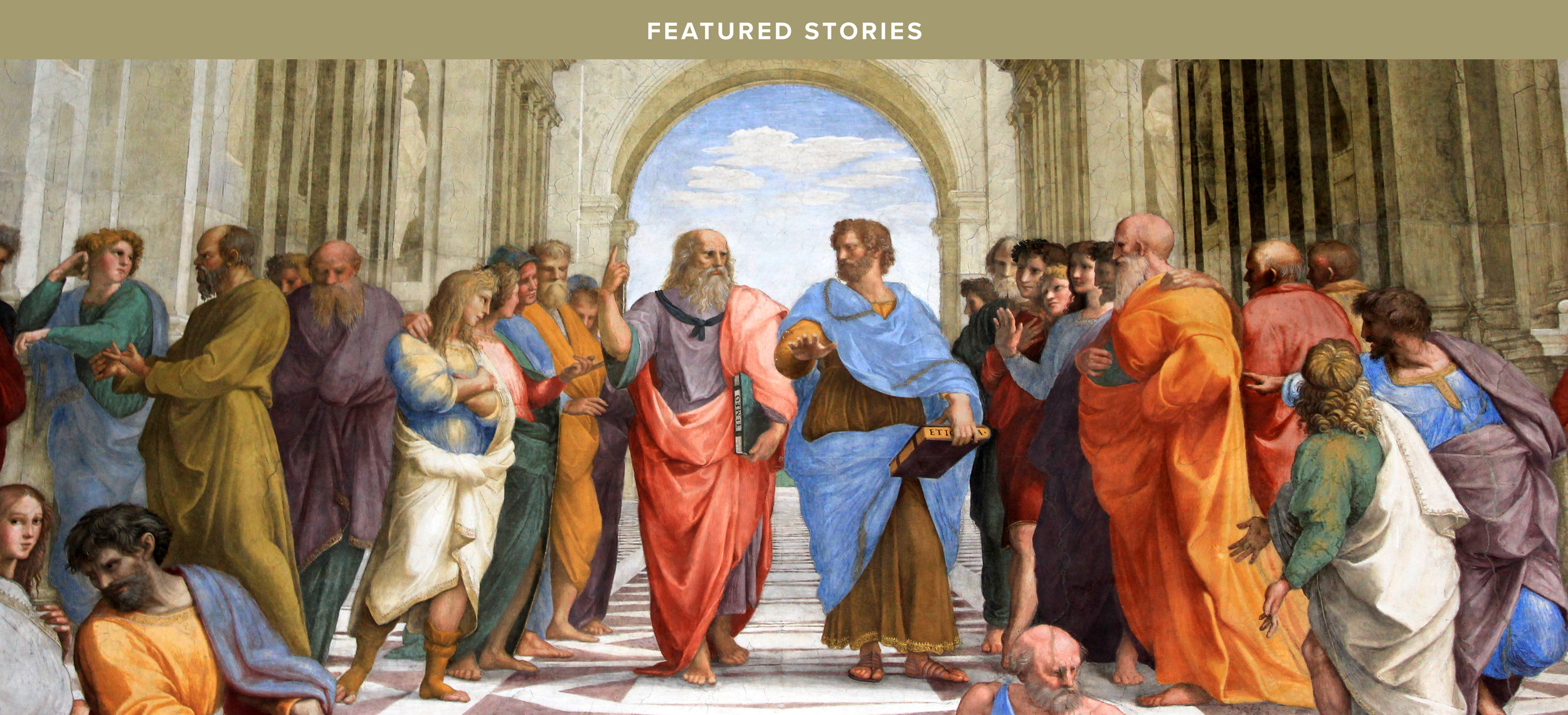

It seems that the notion of “Hellenization” is catching people’s imagination. A few years ago, I was listening to a radio program in which a Dominican priest, Fr. Gabriel Gillen, said that "before we can have a New Evangelization, we need to have a new Hellenization." I thought this was a fantastic statement. Historically speaking, Hellenization refers to the spread of Greek language and customs after the conquests of Alexander the Great. Culturally speaking, Hellenization is the spread of Greek philosophy, mainly the thought of Plato and Aristotle, throughout Europe and the Middle East.

So why do we need a new-Hellenization before we can have a New Evangelization? Fr. Gillen was saying that we have lost the tools for rational discourse which Plato & Aristotle gave us. Plato's notion of the forms and transcendence and Aristotle's structure of matter and form are basic intellectual tools. These tools were applied to Revelation and helped us understand the Faith. In fact, many scholars agree that the “marriage between Athens and Jerusalem” was providential and essential for the development of Christian theology. Without these tools it is extremely difficult to reach people with the truths of the Faith, even when they are familiar with Christianity.

More recently, Michael Hanby, a professor at the John Paul II Institute in DC, wrote a piece in First Things on the "De-Hellenization of Christianity." "The essence of de-Hellenization,” he wrote, “is a loss of 'the superiority of the immutable over the changeable,' a superiority, paradoxically, that ensures that the mundane things of this world... are invested with inherent meaning and intelligibility as symbol and image of the immutable." In other words, we have lost the understanding and desire for the transcendent. Hanby continues: “In theological terms, this means the inevitable loss of the transcendent otherness and holiness of God, whose subjective correlate is ‘the fear of the Lord.’” For the average Church-goer, this means we have lost the ability to see mystery and meaning in the symbols and rituals of our Faith, such as that to be found in the Mass.

Hanby’s thinking was echoed by a young priest from Milwaukee, who wrote about his experience working in a parish. Fr. Jacob Strand writes, “Teaching the elementary school students and ministering the sacraments were two of my principal responsibilities. They also were experiences that disclosed a regrettable truth. Neither education nor the sacramental liturgy captured parishioners’ minds and hearts: more often than not, both these experiences bored them.” Fr. Strand’s spiritual and intellectual search to answer the disconnect between his parishioners and the riches of the Faith led him to the British thinker and author, Stratford Caldecott.

Stratford Caldecott devoted two books to the revival of classical education and the recovery of the transcendent through the cultivation of Truth, Beauty and Goodness. Thus for Caldecott, one of the strongest answers to the De-Hellenizaton that Hanby laments is the revival of classical education. Caldecott’s first book on classical education is titled Beauty in the Word: Rethinking the Foundations of Education. In this book, Caldecott offers a reflection on the Trivium, a traditional three-fold approach to education of Grammar, Logic and Rhetoric. In Caldecott’s second book, titled Beauty for Truth’s Sake: On the Re-enchantment of Education, he reflects on the Quadrivium (Arithmetic, Geometry, Astronomy and Music), which have been traditionally combined with the three phases of the Trivium to comprise the seven liberal arts.

On one level, throughout both books, Caldecott endeavors to counter the Cartesian inward turn to the self that basically inspires all modern approaches to education. He relies heavily on St. John Paul II and quotes Fides et Ratio: “Wherever men and women discover a call to the absolute and transcendent, the metaphysical dimension of reality opens up before them: in truth, in beauty, in moral values, in other persons, in being itself, in God.” Discovery begins in looking outside of one-self.

On a deeper level, Caldecott emphasizes that education must be both personal and metaphysical, for the ultimate object of education is the Second Person of the Trinity, Who is both Christ and the Word. Caldecott writes: “We must be able to perceive the inner, connecting principles, the intrinsic relations, the Logoi, of creation. For this the eye of the poet, or of the mystic, is needed. Education should lead to contemplation.”

So this is the challenge for the classical education movement. It is true that the immersion of young students in the people and places of the classical world gives them the rational tools to better understand the Faith. However, this is not enough. Classical education has to be much more. In order for classical education to be the answer to de-hellenization, it must be both personal and metaphysical. Classical schools will only achieve this through a commitment to the Divine Liturgy as a central part of their educational mission.